One of the best parts of my college education was the almost weekly appearance of prominent speakers at UCLA. For the most part these were well known people - recent Time magazine covers - and being able to see and hear, and in some cases talk to, the human beings behind the mythical characters portrayed on television, magazines, and books when a long way to making me realize that, in fact, famous, even great, people, were first of all just people. Two of the most memorable were Margeret Mead and George Wallace. Sitting on the floor around the famed anthropologist with 20 other students and talking to her was like leaving reality and entering into the magical world of books and media.

Wallace was governor of Alabama. Alabama was seething with demonstrators. Police and marchers were in daily conflict over the contradiction between the US Constitution and the Jim Crow laws of the South. The shocking images of dogs attacking, and police beatings unarmed and peaceful demonstrators were on television every night. Wallace was clearly one of the devil's emissaries. What could he possibly say or do that could change our minds? Obviously, nothing. When I got to the auditorium about an hour early - I knew it would be crowded - the first three or four rows were already filled with Black students. By the time he came to the stage, the room was packed and there was a collective tension and anticipation. I don't remember what he said, but within five minutes of taking the stage, Wallace's humor, charisma, and obvious intelligence had disarmed the audience. We laughed at his jokes and we listened to his words. We didn't agree with his beliefs about segregation, but there was obviously much more to this man than I, and I'm sure most of the audience, was prepared for. And it made it much easier to understand why the people of Alabama had elected him. It had a profound impact on how I evaluated people from then on - particularly those I only knew through the media. It began opening me to see the myths we absorb as we grow up. As any people grow up. I'd bought into all the demonizing of this man. Don't misunderstand me here, I still believe the legally sanctioned segregation was abhorrent. But I learned that human beings were much more complicated than I'd ever imagined.

So I'm pleased to say that in the last few years, the University of Alaska Anchorage has hosted far more prominent speakers on campus. Jared Dimond, Francis Collins, and Alan Lightman all gave very powerful presentations last year. While these aren't speakers of the same national prominence, they are a start. Of course today, campus speaking has become much more of a business rather than an honor and public service, with the most sought after speakers earning tens of thousands of dollars for a presentation. Nevertheless, it is still important for us to see and hear in person, the people we see on the flat screen.

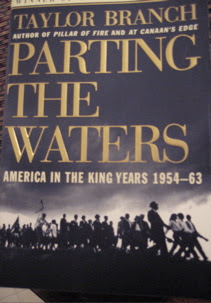

In any case, tonight we heard Taylor Branch speak. He said a number of significant things. What he said about the importance of myth and stories in our culture and how they shape what we think and do goes right to the heart of my last publications. He also told stories of his childhood - how his stories shaped his knowing of the world. The black employee at his father's Dry Cleaners with whom his father had a real friendship, and how Taylor joined the two of them at Atlanta Cracker baseball games. Except that at the stadium, the employee had to sit in the colored section while he and his dad sat in the white section. How shocked he was when his father spoke at the employee's funeral, and cried. And how he somehow knew as a child that this topic of race relationships was not to be discussed. Harold Napolean talks about great silence among Alaska Natives, how the great epidemics that wiped out Alaska Native villages in the late 19th and early 20th Century were also not spoken about. Which was also true about children of holocaust survivors generally not hearing from their parents' stories. I know I never asked about what had happened to my grandparents who never got out of Germany. It was a subject that just wasn't to be raised, and I didn't until I was in my twenties.

He also talked about his battles with the academics at Princeton who discouraged him from doing his policy research summer trying to register black voters in rural Georgia, because real research was done at established institutions. And how turning in his summer diary was also frowned on, but he insisted because Washington policy and what he experienced were two totally different realities. This too resonated with how my experiences as a student in Germany and a teacher in rural Thailand taught me - experientially - what my later graduate programs didn't cover. And how, in his case, one faculty managed to help him get parts of his diary published.

And in terms of substance, he argued that there are three American myths that prevent us from seeing the important and positive legacy of the civil rights movement in the United States. Myth 1 - Race is both 'solved' and 'unsolvable.' Once the laws that specifically blocked access to equality were ended, the other actions, like Affirmative Action were too idealistic and ineffective because these things just can't be solved through government. Myth 2 - Politics failed in the 1960's, it overreached itself. Basically, that Government is bad. Myth 3 - Violence is the strength of the US. The importance and contribution of the non-violence of the civil rights movement is not understood or even seen. It's influence in the rest of the word - the non-violent overthrow of the Soviet Union and other Eastern European nations, for example - is not acknowledged.

I've paraphrased these fairly briefly, and don't do him justice here. Though I'm a firm believer that what he is calling myths and stories and narratives are, in fact, often unconscious and uncritcally believed. And when they are wrong, their basic invisibility and the taboo on challenging them, as was the case of segregation in the South, prevents us from even considering other possibilities. One example he gave was how various Southern politicians argued loudly that the only way integregation could come to the South was through violent imposition and this would never succeed. That integration would destroy the South. Branch argued that, in fact, as soon as the blight of forced legal segregation was ended, the South could join the rest of the nation. Major league sports moved into the South. Southern politicians could be considered for President (Johnson, Carter, Clinton, Bush) of the US, and the economy took off. The energy that had been spent enforcing segregation, and the suppressed potential of Black Southerners, were now available for more positve work.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments will be reviewed, not for content (except ads), but for style. Comments with personal insults, rambling tirades, and significant repetition will be deleted. Ads disguised as comments, unless closely related to the post and of value to readers (my call) will be deleted. Click here to learn to put links in your comment.