This is the second week of a MOOC class I'm taking called "Data Exploration And Story Telling" taught by

Alberto Cairo and

Heather Krause.

I'm taking this class because several work sessions at Alaska Press Club conferences (for example this

session with Chrys Wu) have convinced me of the power of being able to extract information from online or otherwise acquired (with permission of course) data bases and then manipulating that data, offers opportunities for really powerful stories.

[For those of you still scratching your head about MOOC, it's

Massive Open Online Course. This class has some 6000 students. And when I write 'manipulate' I mean it in the sense of reorganizing the data so that the meaning of the numbers is easier to understand. But I acknowledge that it is easy to misinterpret the data both accidentally and intentionally.]

Data Journalism seems to be a hot topic these days as large data bases are increasingly becoming available. For me the issue is figuring out how to download them, clean them up, and then play with them to find interesting patterns. That's what I'm hoping to get out of the class.

Here's a link to a

Guardian article on data journalism. Here's a section of that article that is becoming increasingly clear to me

"5. Data journalism is 80% perspiration, 10% great idea, 10% output

It just is. We spend hours making datasets work, reformatting pdfs, mashing datasets together. You can see from this prezi how much we go through before we get the data to you. Mostly, we act as the bridge between the data (and those who are pretty much hopeless at explaining it) and the people out there in the real world who want to understand what that story is really about."

This is both encouraging (I'm not a dummy because I think this looks like a lot of work) and discouraging (because I'm one blogger without a team of folks to help figure this out and do the work.)

Numbers, graphically displayed, can powerful tell stories that are otherwise invisible. I've known this for many years. It can often be relatively simple to prove or disprove someone's idea by getting the numbers. I remember back in the 1980s at the Municipality of Anchorage, a couple of fairly easy projects where data ended or changed the conversation.

One was about the use of pool cars. The Muni had some cars that employees could use to go out on Muni business. We were getting complaints that there weren't enough cars and people were getting turned down. We just asked the person who assigned the cars to log the requests for a month. It turned out that anyone who asked for a car 24 hours in advance, got one. But people who wanted a car in ten minutes sometimes got turned down. That report ended the discussion.

Another study of the people making over $10,000 a year in overtime was sent to all the department heads, just to let them know. This highlighted some departments with high rates and led to more careful monitoring and in some cases to adding positions.

Hospitals have used data on treatment and length of stay and recidivism rates for each doctor's patients in certain units. The data led to doctors making changes in their treatment of patients.

So I know this can be very powerful. We'll see whether I can learn to do this with the tools I have - I've been an Excel holdout, trying to by with Apple's version, Numbers. And there seem to be a number of folks in class who are doing this already as part of their work. And this class seems a little harder to negotiate online than the Coursera class I took in the fall. There are so many forums and comments - which there should be with 6000 students - that it feels a bit like being in jammed train station at rush hour.

And then there's the issue of storytelling. I believe in the power of stories and their importance. But I'm starting to get concerned about how loosely it is being used, and how it can lend to people dismissing the stories as, just that, stories. Something made up.

We're in the era when photos can be easily manipulated by anyone and now video can be manipulated to change the narrative. The use of story lines by media is nothing new. The broader skepticism on the part of the public is also a good thing. But skepticism without the critical skills to assess a story's accuracy is problematic. We're in an era where people shop around until they find the spin that fits their world view, wether it's accurate or not.

And some take full advantage of this. Trump tells whatever story makes him look good and challenges those that don't.

From the LA Times:

Challenged on NBC's "Meet the Press" about Spicer making incorrect claims, Trump advisor Kellyanne Conway made a startling characterization , that Spicer gave "alternative facts."

“You're saying it's a falsehood, and Sean Spicer, our press secretary, gave alternative facts to that,” Conway told host Chuck Todd, who immediately interjected his disbelief over her description.

Conway eventually backed off Spicer's adamant claims and inflated crowd estimates. “I don’t think you can prove those numbers one way or the another,” she said. “There's no way to really quantify crowds."

Alternative facts? No way to really quantify crowds? Really?

If you live in Trump's competitive world where everything is about winning, then facts only matter if they help you win. You challenge the umpire every time he calls you out and every time he calls your opponent safe. Whether you got to the base before the ball did is irrelevant. Instant replay is only your friend if it confirms your claim.

Can data journalism become a form of instant replay? I suspect not. It plays a different role. Instant replay shows us, in slow motion and from a better angle, what we all just saw from different angles at high speed. Data journalism goes through lists of numbers and converts them into visuals that make sense of the numbers. It makes the incomprehensible, comprehensible.

And people will have to become more sophisticated about data collection, about categories used in collecting data, about survey questions, and a whole lot of other things if they're going to be able to evaluate the accuracy of data journalism.

Journalist have to learn those things. In the first week of the class, Heather Krasue offered students a checklist for data:

- Who collected the data?

- How they collected the data?

- Who was included?

- When it was collected?

- Why did they collected the data?

So, between watching the class videos, reading the articles, participating in the forums, and doing the assignments, not to mention playing with my granddaughter and other duties as assigned, keeping up here is getting sketchy.

Here's

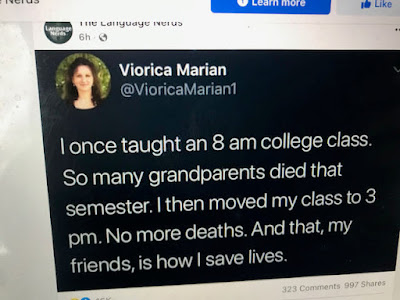

another look at this topic that my friend Jeremy posted on FB the other day.