Contrasting world views is an important underlying factor in the sharp political divisions in the US today. Republicans call this "the culture wars." There are lots of factors to consider, but let's look narrowly at one very important one: differences in people's idea of the relationship between humans and nature.

John Vaillant, in his book Tiger: True Story of Vengeance and Survival (here's a previous post on that book), looks at how differing world views clash in the frontiers of the Russian Far East. His book focuses on the survival of wild tigers, but the process is repeated all over the world with different species and different indigenous peoples.

The modern world came about when humans began to apply science to most human activities including the economy. With science, it was believed, humans were no longer at the mercy of nature. Using science, humans could now control, even conquer nature.

Science has enabled humans to create what in previous times would have been considered miracles. Free enterprise enabled us to make and sell the amazing feats of science. We became gods who could rearrange nature to suit us. But there have been terrible side effects. So let's go to Vaillant's Russian Far East - near Kharbarovsk - to see the contrasting views on nature and humans.

"Prior to the arrival of Chinese gold miners and Russian settlers, there appeared to be minimum conflict between humans and tigers in what is now Primorye. Game was abundant, human populations were relatively small, and there was plenty of room for all in the vast temperate jungles of coastal Manchuria. Furthermore, the Manchus, Udeghe, Nania, and Orochi, all of whom are Tunguisic peoples long habituated to living with tigers, knew their place; they were animists who held tigers in the highest regard and did their best to stay out of their way. But when Russian colonists began arriving in the seventeenth century, these carefully managed agreements began to break down. People in Krasny Yar still tell stories about the first time their grandparents saw Russians: huge creatures covered in red hair with blue eyes and skin as pale as a dead man’s." (141)

Earlier in the book he wrote about how the indigenous populations in other parts of the world - like the Bushmen in the Kalahari desert - who had similar relationships with lions. He also makes comparisons between the Russian Far East and the conquest of North America.

"Some of these newcomers were Orthodox missionaries and though they were unarmed, their rigid convictions took a serious toll on native society. The word “shaman” is a Tungusic word, and in the Far East in the mid-nineteenth century, shamanism had reached a highly evolved state. For shamans and their followers who truly believed in the gods they served and in the powers they wielded, to have them disdained by missionaries and swept into irrelevance by foreign governments and technology was psychically devastating - a catastrophic loss of power and status comparable to that experience by the Russian nobility when the Bolsheviks came to power. (141-142)Anyone familiar with Alaska Native history is familiar with stories of Native drumming and dancing being banned and kids having their mouths washed out with soap for speaking their own languages at school. And I can't help think that part of today's cultural wars are due to the same sense of loss of power and sense of entitlement by those Americans who are threatened by the rapid changes in the world today.

In Primorye, this traumatic process continued into the 1950s. The Udeghe author Alexander Konchuga is descended from a line of shamans and shamankas, and he grew up in their company. “Local authorities did not prohibit it,” he explained. “The attitude was, if you’re drumming at night, that’s your business. But the officials in the regional centers were against it and, in 1955, when I was still a student, some militia came to my cousin’s grandmother. Someone must have snitched on her and told them she was a shamanka because they took away her drums and burned them She couldn’t take it and she hanged herself.” The drum is the membrane through which the shaman communicates with, and travels to, the spirit world. For the shaman, the drum is a vital organ and life is inconceivable without it.

Along with spiritual and social disruption came dramatic changes in the environment. One Nanai story collected around 1915 begins, “Once upon a time, before the Russians burned the forests down . . .” (142)It wasn't until the arrival of foreign settlers with livestock that tiger problems arose. Vaillant met and interviewed Valery Yankovsky and writes about the history of settlement with a focuses on the Yankovsky family.

“. . . the Yankovsky family hadn’t lived in their new home a year before they registered their first losses. Between 1889 and 1920, tigers killed scores of the Yankovskys’ animals - everything from dogs to cattle. Once a tiger dragged one of their hired men from his horse.So similar to whites moving into Indian country in North American, and Westerners colonizing much of the world. There was a sense of their superiority. Manifest destiny. They had better weapons, better ships, and better science created technology, not to mention religion. Many truly believed they were entitled to take over, because of their perceived superiority, and some - particularly the missionaries - believed their presence would "help the natives."

In the eyes of the Russian settlers, tigers were simply four-legged bandits, and the Yankovskys retaliated accordingly. Unlike the animist Udeghe who were native to the region, or the Chinese and Korean Buddhists who pioneered there, the Christian Russians behaved like owners as opposed to inhabiters. As with lion-human relations in the Kalahari, the breakdown began in earnest with the introduction of domestic animals. But it wasn’t just the animals, it was the attitude that went with them. These newcomers arrived as entitled conquerors with no understanding of, or particular interest in, the local culture - human or otherwise. Like their New World counterparts across the Pacific, theirs, too, was a manifest destiny: they had a mandate, in many cases from the czar himself, and they took an Orthodox, Old Testament approach to both property and predators. (148) (emphasis added)

Vaillant compares Yankovsky world view to that of an indigenous inhabitant of the region.

“. . .Even a hundred years later, Ivan Dunkai’s son Vasily’s description of his relationship to the local tigers stands in stark contrast to a Russian settler’s. “You know, there are two hunters in the taiga: a man and a tiger,” he explained in March 2007. “As professional hunters, we respect each other: he chooses his path and I choose mine. Sometimes our paths intersect, but we do not intrude on each other in any way. The taiga is his home; he is the master. I am also a master in my own home, but he lives in the taiga all the time; I don’t.”

This disparity between the Yankovskys and the Dunkais is traceable to a fundamental conflict - not just between Russians and indigenous peoples, but with tigers - around the role of human beings in the natural world. In Primorye, ambitious Russian homesteaders operated under the assumption that they had been granted dominion over the land - just as God had granted it to Noah, the original homesteader:

1. Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth

2. And the fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth

Implicit in these lines from Genesis 9 is the belief that there is no room for two on the forest throne. And yet, in a different context, these words could apply as easily to tigers as they do to humans. In so many words, God puts the earth and all its creatures at their disposal:

3. Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you; even as the green herb have I given you all things. (150)

. . .It is only in the past two hundred years - out of two million - that humans have seriously contested the tiger’s claim to the forest and all it contains. As adaptable as tigers are, they have not evolved to accommodate this latest change in their environment, and this lack of flexibility, when combined with armed, entitled humans and domestic animals, is a recipe for disaster. (151)

The past two hundred years. The onset of the modern world in which science was applied to human enterprise and the market system, articulated by Adam Smith in 1776, began to develop into the industrial revolution.

Mitt Romney seems clearly entrenched in the modern ideal of science helping humans conquer nature, which has led to globe threatening development. Romney referred to this period this week in his talk at the Clinton Global Initiative:

The best example of the good free enterprise can do for the developing world is the example of the developed world itself. My friend Arthur Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute has pointed out that before the year 1800, living standards in the West were appalling. A person born in the eighteenth century lived essentially as his great-great-grandfather had. Life was filled with disease and danger.

But starting in 1800, the West began two centuries of free enterprise and trade. Living standards rose. Literacy spread. Health improved. In our own country, between 1820 and 1998, real per capita GDP increased twenty-two-fold. (emphasis added)While modern medicine and agriculture have improved the lives of many, and living conditions of Europe and the United States improved greatly, those European nations had colonies around the world that gave them cheap resources and labor. The US, itself a colony before it broke off from England, took advantage of the enormous wealth of North America by displacing the indigenous populations and exploiting the resources, with slave labor, with waves and waves of immigrant labor, and with imported, cheap Asian labor.

Also, the world population has increased from a billion in 1804 to over 7 billion in 2012. Yet despite the improvements Romney cites the World Food Programme reports that:

10.9 million children under five die in developing countries each year. Malnutrition and hunger-related diseases cause 60 percent of the deaths;Actually another of their statistics shows that the number of hungry people in the world today is almost as high as the total world population in 1804. So, there is probably much more suffering in the world today than 200 years ago.

- 925 million people do not have enough to eat and 98 percent of them live in developing countries. (Source: FAO news release, 14 September 2010)

And during that period, to achieve the physical standard of living that the most 'developed' countries have, humans have had to destroy the world's forests and oceans and sky, so that most indigenous populations have been either physically or culturally annihilated, and untold numbers of animal, bird, and plant species have gone extinct and more are threatened with extinction at an even faster rate today. See Global Issues, library index, Forest Transitions, or the Sustainable Scale Project for details.

Vaillant's The Tiger details some of that change from living in harmony with nature to the sense of entitlement and dominance over nature in one small part of the world.

Mitt Romney would continue this trend by expanding US businesses into every possible country where they can continue to exploit the resources to the detriment of the inhabitants. Romney, like the Russian Czars and the Soviet bosses, sees this as humans' natural dominance over nature and doesn't seem to consider the possibility that Western colonization and exploitation of African and Asian nations (where most of today's world poverty exists) might have something to do with the poverty in those continents today. To him it's simply the lack of free enterprise, not because they were the victims of free enterprise.

Conditions among indigenous peoples around the world may have been primitive compared to modern Western standards, but most of those cultures had survived intact over the millennia and now many, if not most, have been destroyed or are endangered - usually because their habitats have been devastated by deforestation or other resource extraction by Western business interests. Romney goes on:

"As the most prosperous nation in history, it is our duty to keep the engine of prosperity running—to open markets across the globe and to spread prosperity to all corners of the earth. We should do it because it’s the right moral course to help others." (emphasis added)We are, he tells us, the most prosperous nation in history. And so we have a duty to spread the free market system:

To foster work and enterprise in the Middle East and in other developing countries, I will initiate “Prosperity Pacts.” Working with the private sector, the program will identify the barriers to investment, trade, and entrepreneurialism in developing nations. In exchange for removing those barriers and opening their markets to U.S. investment and trade, developing nations will receive U.S. assistance packages focused on developing the institutions of liberty, the rule of law, and property rights. (emphasis added)Let's see, in order for us to help you, we, the most prosperous nation in history, require you to open your markets to our powerful corporations to take your raw materials (forests, oil, minerals, etc.) with no pesky environmental protections, use your cheaper labor, and sell our products to your citizens.

Explain to me how the new businesses in these most undeveloped countries are going to compete with the businesses in the most prosperous nation in history. Tell me how Romney will keep foreign business interests from bribing the local politicians even more blatantly than they do our politicians. How he will keep them from spoiling their environments and setting up horrible working conditions like in the factory in China Romney bought.

I want to be clear here. I believe that the free market does unleash human energy and creativity and allows the growth of wealth. But it's not a panacea. It comes at a cost. Economists have noted externalities as a failure of free enterprise. These are things like pollution and other side effects businesses do NOT pay for when manufacturing their products, but end up as costs to the society as a whole. As pollution clean up, as health problems, as destroyed forests and cultures.

These externalities are destroying our planet. Free enterprise, without government controls to make corporations assume the costs of those externalities, destroys our natural world and those cultures that don't embrace our economic system.

Romney appears to be the bearer of the philosophy that destroyed the forests in the Russian Far East. It's not the philosophy of free enterprise, because the Soviets destroyed the Russian Far East with the help of the Chinese. Rather it is the philosophy that man can conquer nature rather than man must live in harmony with nature. I'm not excusing Obama in this either, though he does, at least, talk about the need to stop global climate change and protect the environment. But you can't raise enough money to run for national office without the help of all those corporations that want access to foreign markets and easing of government oversight. But Romney seems to believe all this stuff about the great effects of the unbridled market place. Of conquering nature through science. Has he been to Russia lately? Has he inspected the oil fields of the Amazon? Or in Nigeria?

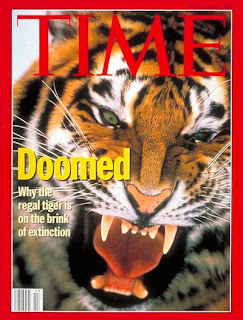

One value of Vaillant's book is to show us up close this clash of values in one location in the world. There are many other books that show how it happened in other locations. In Alaska we see how Russian fur traders did the same thing to indigenous peoples of our coastal areas as they almost brought extinction to the sea otter population. And American whaling ships almost wiped out the whales that summer in Alaska waters. Elsewhere we see it in the depletion of various Atlantic fish species. And the near extinction of wild tigers.

The free enterprise system has to be restrained so that its profit doesn't come from the depletion of the earth's resources. We need world views that understand that for humans and other living things, to survive, we must live in harmony with nature.