"In 1925, Nikolai Baikov calculated that roughly a hundred tigers were being taken out of greater Manchuria annually . . . virtually all of them bound for the Chinese market. . . Between trophy hunters, tiger catchers, gun traps, pit traps, snares, and bait laced with strychnine and bite-sensitive bombs, these animals were being besieged from all sides. Even as Baikov's monograph was going to press, his "Manchurian tiger" was in imminent danger of joining the woolly mammoth and the cave bear in the past tense. Midway through the 1930's, a handful of men saw this coming, and began to wonder just what it was they stood to lose." [From The Tiger, p. 96]

|

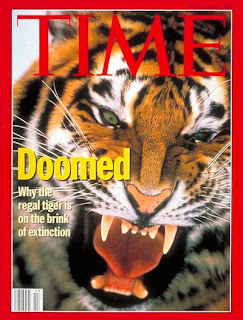

| Image from Time |

I remember reading pessimistic stories about the ultimate demise of wild tigers back in the 1990's like this 1994 Time Magazine cover story.

It seems people just gave up. Accepted that it was inevitable!

The same people who could fly to the moon and Mars, couldn't save their own planet from being plundered. If there were a god, I think it would say, with an eye to the Mars rover, "You can't have another planet until you take care of your own."

I'm reading The Tiger: True Story of Vengeance and Survival by John Vaillant for next Sunday's book club meeting.

I thought I'd share some excerpts.

During the winters of 1939 and 1940, [Lev Kaplanov] logged close to a thousand miles crisscrossing the Sikhote-Alin range as he tracked tigers through blizzards and paralyzing cold, sleeping rough, and feeding himself from tiger kills. His findings were alarming: along with two forest guards who helped him with tracking, estimates and interviews with hunters across Primorye, Kaplanov concluded that no more than thirty Amur tigers remained in Russian Manchuria. In the Bikin valley, he found no tigers at all. With barely a dozen breeding females left in Russia, the subspecies now known as Panthera tigris altaica was a handful of bullets and a few hard winters away from extinction.

Despite the fact that local opinion and state ideology were weighted heavily against tigers at the time, these men understood that tigers were an integral part of the taiga picture, regardless of whether Marxists saw a role for them in the transformation of society. Given the mood of the time, this was an almost treasonous line of thinking, and it is what makes this collaborative effort so remarkable: as dangerous as it was to be a tiger, it had become just as dangerous to be a Russian. [pp. 98-99]

. . . In 1943, at the age of thirty-three, Lev Kaplanov was murdered by poachers in southern Primorye where he had recently been promoted to director of the small but important Lazovski Zapovednik. [p. 102]Primorye is where The Tiger is focused. It starts on December 5, 1997 with an unusual, almost murder, of a hunter named Markov, by a huge tiger. I say murder, because this cat seems to have taken vengeance on this particular man. It was not a simple case of opportunistic hunting by a starving tiger. The book follows Yuri Trush, a member of a government team of game wardens - The Tigers - that protects tigers in the Primorye.

Primorye . . . is about the size of Washington state. Tucked into the southeast corner of Russia by the Sea of Japan, it is a thickly forested and mountainous region that combines the backwoods claustrophobia of Appalachia with the frontier roughness of the Yukon. Industry here is of the crudest kind: logging, mining, fishing, and hunting, all of which are complicated by poor wages, corrupt offiials, thriving black markets - and some of the world's largest cats. [p. 8]Vaillant uses this death to explore Primorye (an incredible biologically unique piece of geography where subarctic and tropic flora and fauna mix), the history of tigers protection in Russia, the relationships between indigenous peoples living in big cat country and their big cat neighbors, and the possibility of saving wild tigers. I like the combination of murder mystery and tiger history, though Vaillant has a chamber of commerce way of making descriptions into dramatic declaratory statements.

Trush's physicality is intense and often barely suppressed. He is a grabber, a hugger, and a roughhouser, but the hands initiating - and controlling - these games are thinly disguised weapons. His fists are knuckled mallets, and he can break bricks with them.This reminds me of all the New Yorkers I've met who only went to the best doctor in the city, sent their kids to the best schools, and shopped at the best market in Manhattan. I was impressed at first, but then it seemed everyone I met did the same thing. I don't doubt that Trush is an amazing man, but he almost sounds like a comic book character in descriptions like this.

But that's a minor criticism. And I'm only a third of the way through the book. Here's a bit more on Russia's contradictory place in world animal conservation.

There is a famous quote: "You can't understand Russia with your mind," and the zapovednik is a case in point. In spite of the contemptuous attitude the Soviets had toward nature, they also allowed for some of the most stringent conservation practices in the world. A zapovednik is a wildlife refuge into which no one but guards and scientists are allowed - period. The only exceptions are guests - typically fellow scientists - with written permission from the zapovednik's director. There are scores of these reserves scattered across Russia, ranging in size from more than sixteen thousand square miles down to a dozen square miles. The Sikhote-Alin Zapovednik was established in 1935 to promote the restoration of the sable population, which had nearly been wiped out in the Kremlin's eagerness to capitalize on the formerly booming U.S. market. Since then, the role of this and other zapovedniks has expanded to include the preservation of noncommercial animals and plants.

This holistic approach to conservation has coexisted in the Russian scientific consciousness alongside more utilitarian views of nature since it was first imported from the West in the 1860's. At its root is a deceptively simple idea: don't just preserve the species, preserve the entire system in which the species occurs, and do so by sealing it off from human interference and allowing nature to do its work. It is, essentially, a federal policy of enforced non-management directly contradicting the communist notion that nature is an outmoded machine in neeed of a total overhaul. Paradoxically, the idea not only survived but, in some cases, flourished under the Soviets: by the late 1970's, nearly 80 percent of the zapovednik sites originally recommended by the Russian Geographical Society's permanent conservation commission in 1917 had been protected (though many have been redued in size over the years.) [pp. 97-98]

If it were merely hunting and habitat destruction that threatened the tiger and the polar bear and the rhinoceros and the countless other smaller species, I would say that it was possible for humans to save them. Possible, but not necessarily likely. But given the global climate change, another collective by product of how humans treat their planet, I have grave doubts. But we shouldn't give up.

Today, "The Tiger in the Sikhote-Alin" [Nikolai Baikov's 1925 monograph] remains a milestone in the field of tiger researh, and was a first step in the pivotal transformation of the Amur tiger - and the species as a whole - from trophy-vermin to celebrated icon. In 1947, Russia became the first country in the world to recognize the tiger as a protected species. However, active protection was sporadic at best and poaching and live capture continued. In spite of this, the Amur tiger population has rebounded to a sustainable level over the past sixty years, a recovery unmatched by any other subspecies of tiger. Even with the upsurge in poaching over the past fifteen years, the Amur tiger has, for now, been able to hold its own.A telling side-effect of the crash prior to this recovery, one caused in part by trophy hunters, is that today's Amur tiger is not as big as the older ones were. With a lesson that Alaskans should pay attention to, Vaillant writes:

It wouldn't be the first time this kind of anthropogenic selection has occurred: the moose of eastern North America went through a similar process of "trophy engineering" at roughly the same time. Sport hunters wanted bull moose with big antlers, and local guides were eager to accommodate them. Thus, the moose with the biggest racks were systematically removed from the gene pool while the smaller-antlered bulls were left to pass on their more modest genes, year after year.

Humans, when they believe something is unfair and wrong, can do amazing things. The fact that there are still Siberian tigers, and that their population is healthier than it was, is an example. Those who know, now need to convince those who still doubt, and we can save many of the species otherwise destined for extinction.

There are many, many people working to save the tiger and other species. We aren't helpless. You aren't powerless. You can help save endangered species. For inspiration and ways you can help, check out

- Save the tiger crusader Steve Galster

- The Wildlife Alliance

- The New York Times says the US has no system for tracking the 5000 captive tigers in the US

- Pantera

And here's a video from the World Wildlife Foundation:

*The market is an important and valuable part of human economy, but it isn't the panacea for all problems some proclaim. (The world is too complex for panaceas.) Milton Friedman himself listed market failures that need to be regulated by government. One, he called "neighborhood effects" and others renamed 'externalities.' These are the costs to society that the producer doesn't pay - the pollution and other environmental damage for example that isn't factored into the price of the product because the manufacturer doesn't have to pay for it. Destruction of habitat to the extent that species are endangered is another externality as is the extinction caused by over hunting - as nearly happened to sea otters and sable and whales. Government regulation is necessary to counteract market failures. (I know, there are those who say the regulations are worse than the problem, but killing off the remaining big (and small animals) is not the price we should have to pay to let entrepreneurs make money. Plus, such an externality isn't an efficient use of our resources which it is why market economists label externalities market failures.)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments will be reviewed, not for content (except ads), but for style. Comments with personal insults, rambling tirades, and significant repetition will be deleted. Ads disguised as comments, unless closely related to the post and of value to readers (my call) will be deleted. Click here to learn to put links in your comment.