In Dante's 14th Century The Inferno, the poet recounts his tour through hell led by Virgil. At that time there was a political divide between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire. From Cliff Notes:

"The cause of this struggle was the papal claim that it also had authority over temporal matters, that is, the ruling of the government and other secular matters. In contrast, the HRE maintained that the papacy had claim only to religious matters, not to temporal matters.

In Dante's time, there were two major political factions, the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. Originally, the Ghibellines represented the medieval aristocracy, which wished to retain the power of the Holy Roman Emperor in Italy, as well as in other parts of Europe. The Ghibellines fought hard in this struggle for the nobility to retain its feudal powers over the land and the peopleIn contrast, the Guelphs, of which Dante was a member, were mainly supported by the rising middle class, represented by rich merchants, bankers, and new landowners.0 They supported the cause of the papacy in opposition to the Holy Roman Emperor."

It's much more complicated. You can go to the link to read more.

But these are human beings struggling over power. As the then 'people of today' [Is there a better way to say this? The people on the border of the future perhaps?] and in one of the world's then power centers, it's clear they probably saw themselves as smarter than people in the past and in other parts of the world. Part of the illusion 'people of today" have is that they 'knew' about things people before them didn't know about. And as humans, their thoughts are relevant to us still today.

We in the US are in a similar situation. We are at the cutting edge of technology and tend to believe we're smarter than people in the past. And many, if not most, US folks feel superior to the rest of the world.

This is, of course, a gross simplification, and I confess my ignorance of Dante's times. But I do know that the human capacity for thought and emotion hasn't changed much in the last thousand years. There were brilliant people a thousand years ago as well as people obsessed by power and other human needs. Evolution hasn't made humans smarter in the last few millennia. And we deceive ourselves when we think we are smarter. We may know more, simply because we know of things that happened after our ancestors died, but that doesn't make us smarter or wiser than they were.

Back to The Inferno

I haven't read this book for almost 60 years when I read it in such detail for class, that I got past the modern belief that old poetry is hard and found the beauty and brilliance of it. The short part that I wanted to quote that is in the title of this post, as I read carefully, is from what now appears to me to be a summary of the poetry to come. It appears, though I'm not certain, that the translator has written a brief description of the content before he presents the poetry itself. I'd note that the translator is John Ciardi, who readers may remember used to do short commentaries on NPR.

As I looked online, I also found a copy of The Inferno, but it has been completely rendered in prose. But that may help the reader.

So instead of just citing the one line I'd originally intended, I'm going to give you all of Canto VIII. First I'll give you the online version, which is more like a Cliff Notes rendition. I'll do this in sections.

Then I'll give you John Ciardi's description (I think that's what it is). And finally I'll give you the poetry itself, which by then, should make sense. I think you'll find the verse itself much easier to follow this way, though in fact, it isn't all that difficult. We're doing all of Canto VIII.

Ciardi:

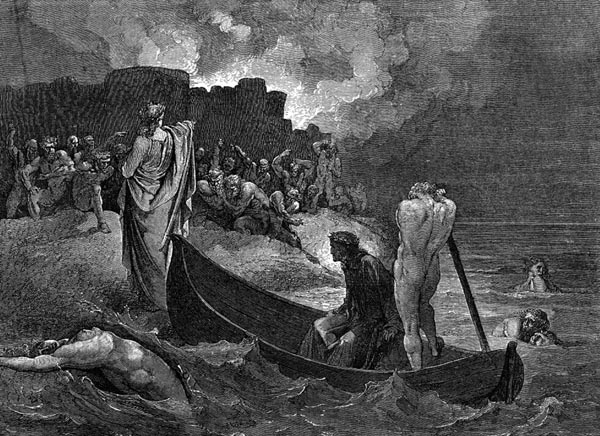

"The Poets stand at the edge of the swamp, and a mysterious signal flames from the great tower. It is answered from the darkness of the other side, and almost immediately the Poets see PHYLEGYAS, the Boatman of Styx, racing toward them across the water, fast as a flying arrow. He comes avidly, thinking to find new souls for torment, and he howls with rage when he discovers the Poets. Once again however, Virgil conquers wrath with a ward and Phlegyas reluctantly gives them passage."

From the online version: [I'd note this is available for public use]

Inferno Canto VIII:1-30 The Fifth Circle: Phlegyas: The Wrathful

I say, pursuing my theme, that, long before we reached the base of the high tower, our eyes looked upwards to its summit, because we saw two beacon-flames set there, and another, from so far away that the eye could scarcely see it, gave a signal in return. And I turned to the fount of all knowledge, and asked: ‘What does it say? And what does the other light reply? And who has made the signal?’ And he to me: ‘Already you can see, what is expected, coming over the foul waters, if the marsh vapours do not hide it from you.’

No bowstring ever shot an arrow that flew through the air so quickly, as the little boat, that I saw coming towards us, through the waves, under the control of a single steersman, who cried: ‘Are you here, now, fierce spirit?’ My Master said: ‘Phlegyas, Phlegyas, this time you cry in vain: you shall not keep us longer than it takes us to pass the marsh.’

Phlegyas in his growing anger, was like someone who listens to some great wrong done him, and then fills with resentment. My guide climbed down into the boat, and then made me board after him, and it only sank in the water when I was in. As soon as my guide and I were in the craft, its prow went forward, ploughing deeper through the water than it does carrying others.

And now for our first taste of Ciardi's rendition of the poetry into English:

[Other than taking a picture of the pages in the book, this use of bullets was the easiest way I could render the structure of the verses, but rest assured, the original doesn't have the bullets, just the form of one main line and two sub-lines.]

- Returning to my theme, I saw we came

- to the foot of a Seat Tower; but long before

- we reached it through the marsh, two horns of flame

- flared from the summit, one from either side,

- and then, far off, so far we scarce could see it

- across the mist, another flame replied

- I turned to that see of all intelligence

- saying: "What is this signal and counter-signal?

- Who is it speaks with fire across this distance?

- And he then: "Look across the filthy slew:

- you may already see the one they summon,

- if the swamp vapors do not hide him from you."

- Now twanging boxspring ever shot an arrow

- that bored the air it rode dead to the mark

- more swiftly than the fling skiff whose prow

- shot toward us over the polluted channel

- with a signle steersman at the helm who called:

- "So, do i have you at last, you whelp of hell?"

- "Phlegyas, Phlegyas," said my Lord and Guide,

- "this time you waste your breath: you have us only

- for the time it takes to cross to the other side."

- Phlegyas, the madman, blue his rage among

- those muddy marshes like a cheat deceived,

- or like a fool at some imagined wrong.

- My Guide, whom all the fiend's noise could not nettle,

- boarded the skiff, motioning me to follow;

- and not till I stepped aboard did it seem to settle

- Into the water. At once we left the shore,

- that ancient hull riding more heavily

- than it had ridden in all of time before.

"As they are crossing, a muddy soul rises before them, it is FILIPPO ARGENTI, one of the Wrathful. Dante recognizes him despite the filth with which he is covered, and he berates him soundly, even wishing to see him tormented further. Virgil approves Dante's disdain and, as if in answer to Dante's wrath, Argenti is suddenly set upon by all the other sinners present, who fall upon him and rip him to pieces."

Before going on, I'd note this context Dante's anger toward Filippo Argenti from Fandom:

"In history, Argenti gained the animosity of Dante Alighieri; the two were on opposite sides of the civil war between the Black Guelphs and White Guelphs. The most popular reason given for this mutual hatred is that Argenti opposed Dante's return to Florence, and while the poet was in exile, he took all of Dante's possessions for himself. As such, Dante writes of his enemy being placed the fifth circle of Hell among the Wrathful after death."

And then back to the online version:

Inferno Canto VIII:31-63 They meet Filippo Argenti

While we were running through the dead channel, one rose up in front of me, covered with mud, and said: ‘Who are you, that come before your time?’ And I to him: ‘If I come, I do not stay here: but who are you, who are so mired?’ He answered: ‘You see that I am one who weeps.’ And I to him: ‘Cursed spirit, remain weeping and in sorrow! For I know you, muddy as you are.’

Then he stretched both hands out to the boat, at which the cautious Master pushed him off, saying: ‘Away, there, with the other dogs!’ Then he put his arms around my neck, kissed my face, and said: ‘Blessed be she who bore you, soul, who are rightly indignant. He was an arrogant spirit in your world: there is nothing good with which to adorn his memory: so, his furious shade is here. How many up there think themselves mighty kings, that will lie here like pigs in mire, leaving behind them dire condemnation!’

And I: ‘Master, I would be glad to see him doused in this swill before we quit the lake’. And he to me: ‘You will be satisfied, before the shore is visible to you: it is right that your wish should be gratified.’ Not long after this I saw the muddy people make such a rending of him, that I still give God thanks and praise for it. All shouted: ‘At Filippo Argenti!’ That fierce Florentine spirit turned his teeth in vengeance on himself.

And now the verses themselves from Ciardi:

- And as we ran on that dead swamp, the slime

- rose before me, and from it a voice cried:

- "Who are you that come here before your time?"

- And I replied: "If I come, I do not remain.

- But you, who are you so fallen and so foul?"

- And he: "I am one who weeps." And I then:

- "May you weep and wail to all eternity,

- for I know you, hell-dog filthy as you are."

- Then he stretched both hands to the boat, but warily

- the Master shoved him back, crying, "Down! Down!

- with the other dogs!" Then he embraced me saying:

- "Indignat spirit, I kiss you as you frown.

- Blessed be she who bore you. In world and time

- this one was haughtier yet. Not one unbending

- graces his memory. Here he is shadow in slime.

- How many living now, chancellors of wrath,

- shall come to lie here yet in this pigmire,

- leaving a curse to be their aftermath!"

- And I: "Master, it would suit my whim

- to see the wretch scrubbed down into swilll

- before we leave this stinking sink and him."

- And he to me: "Before the other side

- shows through the mist, you shall have all you ask.

- This is a wish that should be gratified."

- And shortly after, I saw the loathsome spirit

- so mangled by a swarm of muddy wraiths

- that to this day I praise and thank God for it.

- "After Filippo Argenti!" all cried together

- The maddog Florentine wheeled at their cry

- and bit himself for rage. I saw them gather.

- And there we left him. And I say no more.

- But such a wailing beat upon my ears,

- I strained my eyes ahead to the far shore.

"The boat meanwhile has sped on, and before Argenti's screams have died away, Dante sees the flying red towers of Dis, the Capital of Hell. The great walls of the iron city block the way to the Lower Hell. Properly speaking, all the rest of Hell lies within the city walls, which separate the Upper and the Lower Hell.Phlegyas deposits them at a great Iron Gate which they find to be guarded by the REBELLIOUS ANGELS. These creatures of Ultimate Evil, rebels against God Himself, refuse to let the Lowest pass. Even Virgil is powerless against them, for Human Reason by itself cannot cope with the essence of Evil. Only Divine Aid can bring hope. Virgil Accordingly sends up a prayer for assistance and waits anxiously for a Heavely Messenger to appear."

And as I get to this point, and look at the verse coming below, this language about human reasoning being unable to persuade Evil, is missing, though the idea that God can open the gates is there.

And now back to the online version

Inferno Canto VIII:64-81 They approach the city of Dis

We left him there, so that I can say no more of him, but a sound of wailing assailed my ears, so that I turned my gaze in front, intently. The kind Master said: ‘Now, my son, we approach the city they call Dis, with its grave citizens, a vast crowd.’ And I: ‘Master, I can already see its towers, clearly there in the valley, glowing red, as if they issued from the fire.’ And he to me: ‘The eternal fire, that burns them from within, makes them appear reddened, as you see, in this deep Hell.’

We now arrived in the steep ditch, that forms the moat to the joyless city: the walls seemed to me as if they were made of iron. Not until we had made a wide circuit, did we reach a place where the ferryman said to us: ‘Disembark: here is the entrance.'

Inferno Canto VIII:82-130 The fallen Angels obstruct them

I saw more than a thousand of those angels, that fell from Heaven like rain, above the gates, who cried angrily: ‘Who is this, that, without death goes through the kingdom of the dead?’ And my wise Master made a sign to them, of wishing to speak in private. Then they furled their great disdain, and said: ‘Come on, alone, and let him go, who enters this kingdom with such audacity. Let him return, alone, on his foolish road: see if he can: and you, remain, who have escorted him, through so dark a land.’

Think, Reader, whether I was not disheartened at the sound of those accursed words, not believing I could ever return here. I said: ‘O my dear guide, who has ensured my safety more than the seven times, and snatched me from certain danger that faced me, do not leave me, so helpless: and if we are prevented from going on, let us quickly retrace our steps.’ And that lord, who had led me there, said to me: ‘Have no fear: since no one can deny us passage: it was given us by so great an authority. But you, wait for me, and comfort and nourish your spirit with fresh hope, for I will not abandon you in the lower world.’

So the gentle father goes, and leaves me there, and I am left in doubt: since ‘yes’ and ‘no’ war inside my head. I could not hear what terms he offered them, but he had not been standing there long with them, when, each vying with the other, they rushed back. Our adversaries closed the gate in my lord’s face, leaving him outside, and he turned to me again with slow steps. His eyes were on the ground, and his expression devoid of all daring, and he said, sighing: ‘Who are these who deny me entrance to the house of pain?’ And to me he said: ‘Though I am angered, do not you be dismayed: I will win the trial, whatever obstacle those inside contrive. This insolence of theirs is nothing new, for they displayed it once before, at that less secret gate we passed, that has remained unbarred. Over it you saw the fatal writing, and already on this side of its entrance, one is coming, down the steep, passing the circles unescorted, one for whom the city shall open to us.’

- "My son, the Master said, "the City called Dis

- lies just ahead, the heavy citizens,

- the swarming crowds of Hell's metropolis."

- And I then: "Master, I already see

- the glow of its red mosques, as if they came

- hot from the forge to smolder in this valley."

- And my all-knowing Guide: "They are eternal

- flues to eternal fire that rages in them

- and makes them glow across this lower Hell."

- And as he spoke we entered the vast moat

- of the sepulchre. Its wall seemed made of iron

- and towered above us in our little boat.

- We circled through what seemed an endless distance

- before the boatman ran his prow ashore

- crying: "Out! Out! Get out! This is the entrance."

- Above the gates more than a thousand shades

- of spirits purged from Heaven for its glory

- cried angrily: "Who is it that invades

- Death's Kingdom in his life?" My Lord and Guide

- advanced a step before me with a sign

- that he wished to speak to some of them aside.

- They quieted somewhat, and one called, "Come,

- but come alone. And tell that other one,

- who thought to walk so blithely through death's kingdom,

- he may go back along the same fool's way

- he came by. Let him try his living luck.

- You who are dead can come only to stay."

- "O my beloved Master, my Guide in peril,

- who time and time again have seen me safely

- along this way, and turned the power of evil,

- stand by me now," I cried, "in my heart's fright.

- And if the dead forbid our journey to them,

- let us go back together toward the light."

- My Guide then, in the greatness of his spirit:

- "Take heart. Nothing can take our passage from us

- when such a power has given warrant for it.

- Wait here and feed your soul while I am gone

- on comfort and good hope; I will not leave you

- to wander in this underworld alone."

- So the sweet Guide and Father leaves me here,

- and I stay on in doubt with yes and no

- dividing all my heart to hope and fear.

- I could not hear my Lord's words, but the pack

- that gathered round him suddenly broke away

- howling and jostling and went pouring back,

- slamming the towering gate hard in his face.

- That great Soul stood alone outside the wall.

- Then he came back; his pain showed in his pace.

- His eyes were fixed upon the ground, his brow

- had sagged from its assurance. He sighed aloud:

- "Who has forbidden me the halls of sorrow?"

- And to me he said: "You need not be cast down

- by my vexation, for whatever plot

- these fiends may lay against us, we will go on.

- This insolence of theirs is nothing new:

- they showed it once at a less secret gate

- that still stands open for all that they could do-

- the same gate where you read the dead inscription;

- and through it at this moment a Great One comes.

- Already he has passed it and moves down

- ledge by dark ledge. He is one who needs no guide,

- and at his touch all gates must spring aside."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments will be reviewed, not for content (except ads), but for style. Comments with personal insults, rambling tirades, and significant repetition will be deleted. Ads disguised as comments, unless closely related to the post and of value to readers (my call) will be deleted. Click here to learn to put links in your comment.