Malcolm Gladwell's Outliers: The Story of Success offers a challenge to the belief that all you need are talent and hard work. It offers a mental challenge for those who are successful and take all the credit for themselves. Or aren't and take all the blame.

When Obama said recently "If you’ve got a successful business, you didn’t build that, somebody else made that happen" he was echoing the sentiment of the book, though that single sentence, out of context, certainly gave the Romney team lots to work with. He should have added "all by yourself" and left off the 'somebody else made that happen.' But if you heard the whole piece, you know he meant it right.

" If you’ve been successful, you didn’t get there on your own. You didn’t get there on your own. I’m always struck by people who think, wow, it must be because I’m so smart. There are a lot of smart people out there. It must be because I worked harder than anybody else. Let me tell you something. There are a lot of hardworking people out there. If you were successful, somebody along the line gave you some help. There was a great teacher somewhere in your life. Somebody worked to create this unbelievable American system that we have that allowed you to thrive. Someone invested in roads and bridges. If you’ve got a successful business, you didn’t build that, somebody else made that happen." [For the video click here.]Now that my book club's discussion of Outliers is over let's see if I can give a more thorough look at the book than I did in the previous post that highlighted just one section.

First, the basic argument of Outliers is simple, but not quite straightforward.

Second, and more problematic, is that the proof he offers is a series of case studies. The cases support his argument, but don't prove it.

Some of the cases are strong and well supported by data - like the hockey players' birthdates. Others are incomplete (though detailed) and vague, thus open to other interpretations.

So let me first try to offer the basic argument and then go through the some of case studies. Even if they aren't clear proof, they are all interesting and raise interesting questions.

The Basic Argument (as I see it)

- Among the United States' most fundamental beliefs are

- the self-made man. If you are smart and/or talented and work hard, you can succeed.

- people who achieve amazing feats - star athletes, star entrepreneurs, star musicians - are 'outliers'. That is they fall statistically on the far end of the bell curve. They are exceptions. (Which somewhat contradicts the idea that anyone can succeed.)

- These are myths, at least to some extent.

- achieving recognized greatness depends on

- having 10,000 hours of experience, not just innate genius or talent

- being at the right place at the right time

- cultural background which prepares individuals and/or privileges them

Support

Now let's look at the cases that most strongly support his argument.

1. 10,000 hours - this was the subject of my previous post on this, you can get more details there. He basically takes a study of musicians that says 10,000 hours of serious practice is the threshold separating those who succeed big and those who don't. It's not special genius, it's the work. He gives the example of the Beatles working 8 hours a day, seven days a week playing in Hamburg strip clubs that gave them the 10,000 hours that pushed them beyond the average band. He cites Bill Gates getting access to a time-share computer in high school at a time when most colleges were still using punch cards as an example of someone who got his 10,000 hours in before anyone else and thus was ready to excel in the new world of ubiquitous computers.

He's not saying talent doesn't help, but the real demarcation between those who become great is the 10,000 hours. And, those 10,000 hours include hard work. But that's not enough. Gladwell cites K. Anders Ericsson on the 10,000 hours rule for developing expertise and then extrapolates that to other areas.

2. Being at the right place at the right time. His best example here is Canadian hockey players. The best are overwhelmingly those who were born in January, February, March, and April, because January 1 is the cut off for each year's new kids in school hockey. And for the 9 and 10 year olds, a year's difference is a lot in terms of size and ability. So the oldest kids, those born in the first three months, start out better, so they get more game time, more positive attention from the coaches, and generally more help and recognition that they are 'better.' This extra attention, Gladwell writes, actually makes them better in a few years. They are the ones who get their 10,000 hours. Since there should be a more equal annual distribution of hockey skill, this argument is pretty persuasive and got most media attention when the book came out in 2008. I covered this in more detail in the previous post too.

3. Culture. The example that seemed to have the most objective basis was Korean Airlines pilots. After a series of crashes, KAL had to examine why its pilots were crashing planes more than other airlines' pilots. It turned out that Korean culture is one of the most hierarchically deferential. Co-pilots were never able to directly confront the captain when they thought the captain was making an error. They made very indirect hints. With retraining led by Delta Airlines' David Greenberg, the pilots learned to overcome their culturally induced hierarchical deference so that co-pilots could confront captains in the cockpit. A particularly telling comment (it's hard to find the data behind the comments because the notes in the back are sparse and there's no bibliography) is that most plane crashes occur when the captain is flying the plane (the piloting and co-piloting duties, Gladwell says, are split 50-50 between the captain and co-pilot). The explanation is that the captain, when acting as the co-pilot, is much more assertive telling the pilot to make corrections.

A second cultural example, Asian dominance in international math exams, is interesting, but the cause and effect relationship is harder to prove. (At least with the KAL example the explanation was tested through the retraining.) He's arguing on two levels:

- Growing rice establishes a culture of hard work and perseverance that causes Asian students to spend more time on their math homework

- Chinese (and other Asian) words for numbers better express their numerical value and thus Chinese kids learn them faster and learn to do arithmetic faster

- of the relationship between how hard you work and the reward

- it's complex - effectively running a small business, juggling a family workforce, selecting the right seeds, building a sophisticated irrigation system, etc.

- it's autonomous - here he says the landlords, by the 14th or 15th Century practiced a hands-off relationship and merely collected a set rent and gave the tenant farmers autonomy

In the second part of the Chinese cultural example - the impact of language on how we know the world (a topic dear to my heart) - Gladwell argues that Chinese words for numbers make it easier to learn math.

- all the numbers can be said faster than, say English numbers, and the shorter time needed to say the numbers, the more numbers in a list you can remember.

- the structure of the number words is different in Asian languages

- in Chinese

- the teens are ten-one (eleven); ten-two, ten-three, etc. and

- the twenties are two-ten-one; two-ten-two, etc.

- one hundred (bai) and one thousand and ten thousand are all a one syllable words, thus:

- yi-bai-yi (one hundred and one)

"Ask an English-speaking seven-year-old to add thirty-seven plus twenty-two in her head, and she has to convert the words to numbers (37 + 22). Only then can she do the math: 2 plus 7 is 9 and 30 and 20 is 50, which makes 59. Ask an Asian child to add three-tens-seven and two-tens-two, and then the necessary equation is right there. No number translation is necessary: It's five-tens-nine." [The literal translation is three-ten-seven, not 'tens']The language makes doing math much easier than in Western languages. The words for numbers fit the numerical structures and computational functions better. His backup on this is the fact that international tests of school children have Asian kids way out on top, every year.

"On international comparison tests, students from Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan all score roughly the same in math, around the ninety-eighth percentile. The United States, France, England, Germany, and other Western industrialized nations cluster at somewhere between the twenty-six and thirty-six percentile. That's a big difference."

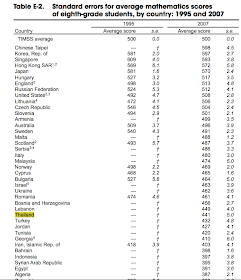

Well, I looked at the TIMSS scores. Here's part of one chart.

|

| Chart from National Center for Educational Statistics - Supplementary Tables PDF link |

OK, the five top countries are Asian: three Chinese speaking countries and South Korea and Japan. Both Japanese and Korean numbers share the Chinese structure for teens, decades, and hundreds. But the Japanese numbers are not all single syllable words. Maybe that's why they are the last of the top Asian countries.

But I would point out that the language of Thailand, which is also a rice producing country - though the paddies aren't as intricate as he describes the terraced Chinese ones - also shares the linguistic numerical advantages of Chinese and Korean and Japanese, yet it is significantly lower on the list than the European countries and the United States.

Ropi, is there something about Hungarians that puts you just below the Asians? Though there is a big gap.

I would also note that such comparative test scores are misleading, because other nations track their students out of the academic tracks at different stages. The lower grades may be more comparable, but by the higher grades, the non-academic tracked students are in vocational schools and don't take the exams. Also, in the US a wider range of students with disabilities often take these sorts of tests (I don't know about the TIMSS though) which can make the US look much worse than it actually is since a different set of kids is tested in different countries. Also, Gladwell uses percentiles whereas the charts I found had raw scores and this way the gap didn't look as large.

If there really is a linguistic advantage for math in Asian languages, that totally changes how we think about the meaning of the test scores and perhaps how we teach math. This argument is more persuasive for me than the rice farming one, though I understand that Gladwell is saying that people in these cultures have a tradition for harder work. But so does every generation of immigrants to the United States and that drive lessens, it seems to me, with each generation. I suspect the story is much more complex than Gladwell portrays it.

There are a number of other interesting cases, but this is long enough. I'll try to do a couple more of his cases in another post. Especially his discussion of cultures of honor and how that explains some Southern behavior.

Basically, Gladwell's book is consistent with Obama's point that successful people are successful because of a combination of things. Obama's blunt "you didn't build that, somebody else did" isn't quite the right message though. And just as Obama supporters use every Romney gaffe, I'm sure the Romney folks enjoyed this one from Obama. But the context of the statement shows he's really saying that no one does it alone. The fact that there are more small business successes in the US than most other countries, for example, makes the point - our system is more supportive of that kind of success.

But I suspect many would disagree with Obama even if his wording were perfect. The Ayn Rand contingent believe the individual is successful on his or her own without help from others. (If that were actually true, then Ayn Rand could have stayed in Soviet Russia and succeeded. They'd say the freedom of the US fosters individual freedom. And I'd say that was what Obama was saying.)

An example of someone who apparently believes that the individual deserves all the credit is described in a Gladwell chapter note about Jeb Bush from S.V. Dáte's Jeb: America's Next Bush:

"In both his 1994 and 1998 runs, Jeb made it clear: not only was he not apologizing for his background, he was proud of where he was financially, and certain that it was the result of his own pluck and work ethic. 'I've worked real hard for what I've achieved and I'm quite proud of it, ' he told the St. Petersburg Times in 1993. 'I have no sense of guilt, no sense of wrongdoing.'I don't think anyone needs to apologize for their family background, but one should be able to acknowledge that being the son of a US Senator/ Vice President/President of the United States might have offered some contacts and access to resources that most people don't have. It's this blindness to one's privileges compared to others that allows rich people to say that the poor are all lazy shirkers. If they weren't they'd all be rich, right?

The attitude was much the same as he had expressed on CNN's Larry King Live in 1992: 'I think, overall, it's a disadvantage,' he said of being the president's son when it came to his business opportunities. 'Because you're restricted in what you can do.'

This thinking cannot be described as anything other than delusional."

Gladwell isn't saying special talent and hard work aren't important. He's saying that lots of people have talent and work hard. But it takes more than that. It also takes luck, being at the right place at the right time with the right individual and cultural skills for the times. That makes sense to me.

Here are the other two posts on Outliers:

Well, first I write about Maths. Hungarian students are considered to be good Mathematicians and your stats are showing the same. However at secondary school I had to answer a lot of stupid questions, so if we are good then I don't know what the rest of the Word is doing. I had a Chinese classmate and their education system is very harsh in Asia so I guess I wouldn't change with them despite the average Korean etc.. is better at Maths than the average Hungarian, no matter how much I like Maths.

ReplyDeleteNow I write a bit about success. This part of the question is a bit senseless to me because you can't really define success. For example passing a Maths exam is not a succes to most of us as a lot of people don't want to be President or Prime Minister either. Success could not be be measured even if the participants had equal motivation to succeed, because there are many things at which physical parameters can help you. For example I was thinking about going to military university to be a tank driver but my dad told me that I am too tall to drive tanks. It was quite disappointing. On the other hand I would have failed on the health check because of my glasses.

Ropi, It seems we agree. Thanks for your example of how family contributes to someone's choice.

ReplyDeleteBTW, did you ever see the posts about Tibor Fischer's book "Under the Frog"? I thought you'd find them (and maybe the book too) interesting. He writes about Hungary, but was born in England three years after his parents left Hungary.

Well, they were right. Once I was on a tank exhibition and I was like 8-10 younger (and smaller) and I could barely sit in so I guess tansk are not for my size. I was learning to drive in a Renault Thalia (http://www.cityszerviz.hu/files/image/tesztek/Renault%20Thalia/renault_thalia_r2.jpg) and it was a nightmare getting in and out. It was a bit dangerous because my head was so close to the ceiling that the inner mirror partly covered my vision and once it was that unfortunate that it covered the street lamp and the traffic signals. Thank God the instructor saw it.

ReplyDeleteNo, I haven't seen that. I will check it later today, but now I am preparing to my SPanish language exam.

It is very interesting how different you use verbs in the US. We learnt British English at school (despite we had American and Canadian teachers as well and it was permitted to use US English) but I will always remember that our Hungarian teachers never liked when someone said "did you ever see" because in British English it would be "have you ever seen". However they were least strict about the pronunciation.

Being tall does have its disadvantages.

ReplyDeleteIt's not an American v. British difference. They have a very subtly different meaning. I tried to write an explanation then looked online to see if I could find a better one.

First, I would say that often they are used to mean the same thing, but there is a difference that is captured mostly by this explanation:

Do you ever . . . ?

this means nowadays because it's the present tense

(and it could be more than once - Do you ever eat yogurt?)

Have you ever . . . ?

this means in your whole life because it's the present perfect tense

Did you ever . . . ? can also be used if you want to focus on

a finished action in the past because it's using the past simple

I meant it this last way - yes or no? Did you read it? "Ever" adds the sense of "in all this time since I posted it until now".

Another example from the internet:

Did you ever go to that restaurant? approximates, to my ear, Did you [finally / eventually] go to that restaurant, as you said you intended to do the last time I spoke to you about it? Did you ultimately carry out your stated intention to go there? [this is what I meant with the question, though not 'as you intended.' I would say, since you didn't comment, I'm not sure if you saw/read it or not. So I'm asking to find out.]

Have you ever gone to that restaurant? approximates, to my ear, Can you say that you were at that restaurant on at least one occasion in your life?

More than you wanted to know, I'm sure.

Thanks for the explanation. It sounds reasonable, but I guess I couldn't convince my teacher if I had told them this during a test. :P

ReplyDeleteOK, the five top countries are Asian: three Chinese speaking countries and South Korea and Japan.

ReplyDeleteKorean numbers

are actually very easy once you get the hang of them. But, because they are so different from English numbers, it is often hard for English speakers to fully understand them at first.

First thing you need to know, there are two sets of numbers in Korean: The pure Korean numbers and the numbers derived from Chinese (called Sino-Korean numbers). Let’s look at the Sino-Korean numbers first, because they are easier:

Sino-Korean Numbers

.

These are the Sino-Korean numbers as provided in Vocabulary:

일 = one

이 = two

삼 = three

사 = four

오 = five

육 = six

칠 = seven

팔 = eight

구 = nine

십 = ten

백 = one hundred

천 = one thousand

만 = ten thousand

With only those numbers, you can create any number from 1 – 10 million. All you need to do is put them together:

일 = one (1)

십 = ten (10)

십일 = eleven (10 + 1)

이십 = twenty (2 x 10)

이십일 = twenty one (2 x 10 + 1)

이십이 = twenty two (2 x 10 + 2)

백 = one hundred (100)

백일 = one hundred and one (100 + 1)

백이 = one hundred and two (100 + 2)

백구십 = one hundred and ninety (100 + 90)

구백 = nine hundred (9 x 100)

천 = one thousand (1000)

천구백 = one thousand nine hundred (1000 + 9 x 100)

오천 = five thousand (5 x 1000)

오천육백 = five thousand six hundred (5 x 1000 + 6 x 100)

만 = ten thousand

십만 = one hundred thousand

백만 = one million

천만 = ten million

The Sino-Korean numbers are used in limited situations. As each of these is taught throughout the upcoming lessons, you will slowly learn when to use the Sino-Korean numbers over the Korean numbers. For now, don’t worry about memorizing when they should be used

, as it will come naturally.

- When counting/dealing with money

- When measuring

- When doing math

- In phone

-numbers

- When talking about/counting time in any way except the hour

- The names of each month

- Counting months (there is another way to count months using pure Korean numbers)

Pure Korean Numbers

.

These are the pure Korean numbers as provided in the Vocabulary:

하나 = one

둘 = two

셋 = three

넷 = four

다섯 = five

여섯 = six

일곱 = seven

여덟 = eight

아홉 = nine

열 = ten

스물 = twenty

서른 = thirty

마흔 = forty

쉰 = fifty

Creating numbers 11-19, 21-29, 31-39 (etc..) is easy, and is done like this:

11: 열 하나 (10 + 1)

12: 열 둘 (10 + 2)

21: 스물 하나 (20 + 1)

59: 쉰 아홉 (5 + 9)

After 60, regardless of what you are doing, pure Korean numbers are rarely used.

The pure Korean numbers are used when:

- You are counting things/people/actions

- Talking about the hour in time

- Sometimes used when talking about months.

Again, don’t worry about memorizing each of those yet. Whenever I talk about numbers, I will tell you which set you are expected to use.